Viola Irene Desmond

July 6, 1914 – February 7, 1965

Canadian businesswoman of Black Nova Scotian descent

This remarkable woman was born and raised in Halifax, Nova Scotia. At a time when most black women worked as housekeepers, or at other menial jobs, Viola Desmond owned and operated her own business. She was a cosmetics pioneer for black women in Atlantic Canada before she ever became a symbol of Nova Scotia’s civil rights movement.

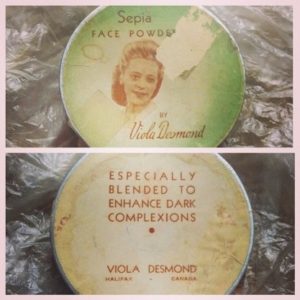

After training in beauty schools in Montreal, Atlantic City, and New York, she returned home and opened a business called Vi’s Studio of Beauty and Culture. It was a beauty parlour and shop that catered to black women where she sold her own line of hair and skin products.

Viola Desmond was not only an astute businesswoman but also an entrepreneur. She created a line of beauty products specifically for black women. Her School of Beauty provided both training and opportunity to black women, who were, because of their colour, not readily accepted for training by other beauty schools.

In 1946, when Viola was on a trip across Nova Scotia to expand her business, she developed car trouble in New Glasgow. While repairs were being made, Ms. Desmond decided to pass the time by going to the movies. She bought a ticket; entered the theatre; and took a seat on the main floor.

Ms. Desmond was not aware that, unlike Halifax theatres, tickets sold to African Canadians in this town were for the balcony while the main floor was reserved solely for White patrons. Once seated, theatre staff approached and demanded that she go to sit in the balcony and – still not understanding – she refused because she could see better from the main floor. Police were summoned immediately and Viola Desmond was, not very gently, dragged out of the theatre injuring her hip in the process.

Without being advised of her rights, Viola was charged and held overnight in jail. Maintaining her dignity, although badly bruised, she sat upright throughout the night, wearing her white gloves which were a sign of sophistication and class at the time.

The following morning, despite having done nothing wrong, and after a sham of a trial, Viola was released from jail after paying a $20 fine and $6 in court costs. She was charged with attempting to defraud the provincial government because of the one-cent difference in the amusement tax charged on tickets sold on the main floor and the balcony. Injured and humiliated, she left immediately for home and for comfort.

But, her battle didn’t stop there. Desmond hired legal counsel and appealed the charge in court — ultimately losing the case. Protests from Nova Scotia’s black community and an appeal to the provincial Supreme Court proved fruitless. Her case didn’t spark the sort of immediate effect seen after Rosa Parks’ 1955 refusal to give up her seat on an Alabama bus; nonetheless, it gnawed at the province’s black community.

Even though Desmond lost her court battle, her story and her vigilant activism through the Nova Scotia Association for the Advancement of Coloured People were important factors in the eventual abolition of Nova Scotia’s segregation laws in 1954.

Sadly, all the attention she received — much of it negative — took a serious toll on Viola. She eventually divorced, shut down her business, and left her home province for Montreal and then New York City in search of a fresh start.

Viola Desmond died alone in 1965 at the age of 50 from internal bleeding. She died without any acknowledgment of racial discrimination in her case and it took decades for the obvious to be admitted.

In 2010 and in the presence of her sister, Wanda Robson, Nova Scotia gave Viola Desmond, posthumously, a free pardon. The black lieutenant-governor, Mayann Francis, signed it into law, saying: “Here I am, 64 years later – a black woman giving freedom to another black woman.”

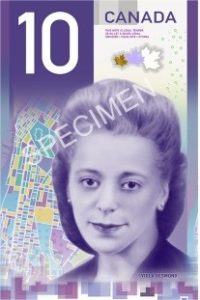

When the Trudeau government opened public consultations to choose an historical woman for the $10 bill, Ms. Desmond was one of five to make the shortlist. In March of 2018 they unveiled the design of the bill: The first vertically oriented banknote in Canada.

Behind Ms. Desmond’s portrait is a map including the stretch of Gottingen Street in north-end Halifax where she opened her salon.

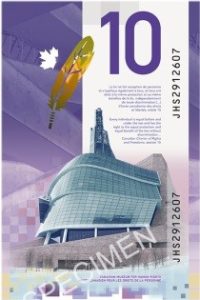

On the other side of the bill is a picture of the Canadian Museum for Human Rights, and an excerpt from the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, section 15, which states:

Every individual is equal before and under the law and has the right to the equal protection and equal benefit of the law without discrimination.

Also on the bill is a gold eagle feather which represents the ongoing journey toward recognizing rights and freedoms for Indigenous Peoples in Canada.

Despite her profound impact on history and her undeniable bravery, Viola Desmond has begun to achieve mainstream recognition only in recent years. In large part this is due to Wanda Robson’s tireless efforts to tell her sister’s story.

Wanda often travelled the country to speak about Viola, and in 2010 she penned a book about her titled Sister to Courage.

**Canadian Heritage Moment Video

References

Historica Canada Heritage Minutes Viola Desmond

Globe staff and wire services

Published November 19, 2018 Updated November 19, 2018

Compiled by Globe staff

With reports from Evan Annett, Laura Stone and The Canadian Press

Gene Herrick/The Associated Press

https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/viola-desmond-bio-1.3886923

How civil rights icon Viola Desmond helped change course of Canadian history

CBC News · Posted: Dec 08, 2016 11:57 AM ET | Last Updated: December 8, 2016