For 120 years, Africville was a primarily Black community located on the outskirts of Halifax, on the south shore of the Bedford Basin. The name “Africville” was never an official designation – residents claimed the name came into use because all the people of colour lived in that part of town.

Discrimination and poverty presented many challenges for this community. Although Halifax collected taxes in Africville, basic municipal services did not follow. Over many years, residents regularly petitioned the city for access to clean water, sewage disposal, garbage removal, electricity, and adequate police protection … but their petitions were largely denied.

Facilities shunned by Halifax cropped up on land disturbingly close to Africville and soon the area filled with undesirable industries such as a fertilizer plant, slaughterhouses, a prison, human feces disposal pits, an Infectious Diseases Hospital, and an open-pit dump.

This shameful treatment of black Nova Scotians is an example of a recently coined term: environmental racism. African Canadians, First Nations, and poor communities have a disproportionate number of dumps and toxic waste sites in their backyards.

Africville was a culturally significant place – a self-sufficient place. It was a strong, vibrant, tight-knit, hard-working community. They may not have had a lot of money, but they weren’t on government assistance either.

They fished the Bedford Basin, planted crops, and worked odd jobs. Dwellings ranged from small houses to shacks for poverty was common and racism allowed only for low wage jobs.

But Africvillians loved their community because it was filled with family, friends, and neighbours who supplied a caring support system.

There were stores, a school, a post office, and the community’s spiritual and social centre: The Seaview United Baptist Church. Away from the city core, residents of Africville could live apart from the racist attitudes of the predominately white population.

Resident Charles R. Saunders wrote that: where the pavement ended and the dirt road began, was a special, protective, out-of-sight place you could call home!

But most Haligonians saw Africville as a ghetto, a blight and an eyesore – a health risk to its inhabitants.

Halifax was growing steadily and the land along the Bedford Basin was particularly desirable for industrial development. In 1964, the City of Halifax voted, with no meaningful consultation with the residents of Africville, to relocate them and to raze the site where their socially solid community stood.

Africvillians strongly opposed relocation, preferring instead to redevelop their existing community. They wanted to improve their homes and to finally obtain normal municipal services – including safe, clean running water.

The projected $800K cost of this redevelopment was prohibitive compared to the estimated $70K to raze and relocate. The proposal to redevelop Africville was rejected and the first land was expropriated in 1964.

Africville was like a warzone. Over the next five years houses disappeared daily and many residents left with what they could carry. Several homeowners found their homes bulldozed with neither their knowledge nor permission. One man returned from a hospital stay to find his house demolished.

In the spring of 1967, their beloved church was destroyed in the middle of the night and this was the death knell for the community. Expropriation sped up as residents took what they could and left.

Halifax used dump trucks and garbage trucks to move residents and their possessions into the city. As you can imagine, the stigma of being from Africville was compounded when families arrived at their new homes on the back of dump trucks and garbage trucks!

Only 14 residents had clear legal titles to their land and they were appropriately recompensed. But the rest, even though they had lived on the site for generations, were given $500 and a promise of follow-up services which, by the way, never materialized.

Most displaced residents found the sum paid for their land and property was enough only for basic or sub-adequate accommodations as some were moved to derelict housing or rented public housing. Many were assigned to apartments in buildings that were slated to be demolished in a few months.

In 1969, the final property was expropriated and demolished and the last of Africville’s 400 residents left.

Sadly, the city had vastly underestimated the $70K cost to raze and relocate and ultimately spent $800K which was roughly equal to the projected cost of redeveloping Africville.

Relocated residents faced racism in their new homes – white neighbours petitioned to keep Black families from living nearby. One relocated Africvillian received a letter threatening to burn his house down if he and his family did not leave. It was signed: from the white people of Hammond Plains.

Jobs were scarce as many companies refused to hire Black people. The overwhelming loss of their community, their homes, and the support of family and friends, made coping with life in the city difficult. Lacking a church or any communal spaces, the displaced residents drifted apart. Some moved to central Canada while many of those who stayed in Halifax were forced to turn to welfare to cover the rising costs of life in the city.

Meanwhile, the land of Africville became private homes, ramps for the A. Murray MacKay Bridge, and the Fairview Container Terminal. The central area of Africville became a dog park.

Despite many challenges, former residents eventually took action and sought justice. The Africville Genealogy Society was formed in 1983 to seek recompense for the suffering caused by the destruction of the community. In 1996, the site was declared a National Historic Site of Canada. In 2010 the City of Halifax made a public apology for the razing of Africville and promised a $3,000,000 settlement – part of which was used to rebuild Seaview Church, which now also serves as the Africville Museum.

The church museum opened in 2012 and the area was renamed Africville Park. Even then, the city thought it knew what was best for the Black community and hired a white woman from out of the province to run the African memorial.

In 2014 Canada Post Corporation issued a commemorative stamp depicting a photograph of seven young girls from Africville against a background of the village.

There are important lessons to be learned from Africville, and I wonder: Have we learned them?

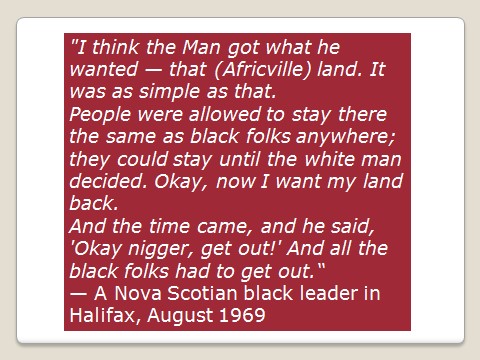

While we’re thinking about that, I’ll give the last word to Africville:

References

- (From the Canadian Museum for Human Rights)

https://humanrights.ca/blog/black-history-month-story-africville

February 23, 2017

- Turning Points: The Razing of Africville an epic failure in urban community renewal

by Paul W. Bennett

Published on November 19, 2017 “I did not see the flowers”

- The Canadian Encyclopedia

www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/africville

article published by Jon Tattrie

January 27, 2014

** Rabble embraces a pro-human rights, pro-feminist, anti-racist queer-positive, anti-imperialist and pro-labour stance and encourages discussions which develop progressive thought.